Scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder that causes an abnormal growth of skin and other connective tissues. The term, derived from Greek, means “hard skin” and refers to the hard, tight skin that develops in many of those affected.

Scleroderma is more common in women, but the disease also occurs in men and children. It affects people of all races and ethnic groups.

In scleroderma, the immune system stimulates cells called fibroblasts to produce too much collagen. The collagen forms thick connective tissue that builds up within the skin and internal organs, such as the heart, lung and kidneys, and can interfere with their functioning. Blood vessels and joints can also be affected.

Types of Scleroderma

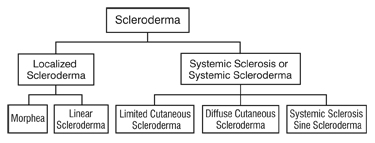

Scleroderma falls into two main classes: localized scleroderma that affects only certain parts of the body and systemic sclerosis that affects the whole body.

A. Localized Scleroderma

Localized scleroderma does not progress to the systemic form of the disease. Localized forms of scleroderma can improve or go away on their own over time, but the skin changes and damage that occur when the disease is active can be permanent. For some people, localized scleroderma is serious and disabling.

There are two basic types of localized scleroderma:

1) Morphea

Morphea refers to local patches of scleroderma.

Morphea can be either localized or generalized. Localized morphea limits itself to one or several patches, ranging in size from ½ inch to 12 inches in diameter. The disease is referred to as generalized morphea when the skin patches become very hard and dark and spread over larger areas of the body. Regardless of the type, morphea generally fades out in 3-5 years. However, people are often left with darkened skin patches and, in rare cases, muscle weakness.

Morphea usually appears in people between the ages of 20 and 40.

2) Linear Scleroderma

Linear scleroderma describes a single line or band of thickened or abnormally colored skin. Usually, the line runs down an arm or leg, but in some people it runs down the forehead. The term term “en coup de sabre”, or “sword stroke,” may be used describe this visible line.

Linear scleroderma usually occurs in children and teenagers.

Some people have both morphea and linear scleroderma.

B. Generalized Scleroderma

Limited cutaneous scleroderma

Limited cutaneous scleroderma tends to develop gradually and affects the skin only in certain areas: the fingers, hands, face, lower arms, and legs.

Most people with limited disease have Raynaud’s phenomenon for years before skin thickening starts. Telangiectasia and calcinosis often follow. Gastrointestinal involvement commonly occurs, and some patients have severe lung problems, even though the skin thickening remains limited.

People with limited disease often have all or some of the symptoms that some doctors call CREST, which stands for the following:

- Calcinosis: The formation of calcium deposits in the connective tissues, which can be detected by x-ray. These deposits can break through the skin and result in painful ulcers.

- Raynaud’s phenomenon: The small blood vessels in the hands or feet overreact to cold or anxiety and reduce blood flow to the fingers or toes. As a result, the hands or feet turn white and cold, then blue. As blood flow returns, they become red. The fingertips and toes have skin damage, such as ulcerations. (NOTE: Raynaud’s phenomenon also occurs in people atherosclerosis or systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus) and in people who are otherwise normal.)

- Esophageal dysfunction: Impaired function of the esophagus that occurs when smooth muscles in the esophagus lose normal movement. In the upper and lower esophagus, the result can be swallowing difficulties. In the lower esophagus, the result can be gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) and inflammation.

- Sclerodactyly: Thick and tight skin on the fingers, resulting from deposits of excess collagen within skin layers. The condition makes it harder to bend or straighten the fingers. The skin may also appear shiny and darkened, with hair loss.

- Telangiectasia: A condition caused by the swelling of tiny blood vessels, in which small red spots appear on the hands and face. Although not painful, these red spots can create cosmetic problems.

Diffuse cutaneous scleroderma

This condition typically comes on suddenly. Skin thickening begins in the hands and spreads quickly and over much of the body, affecting the hands, face, upper arms, upper legs, chest, and stomach in a symmetrical fashion (for example, if one arm or one side of the trunk is affected, the other is also affected). Some people may have more area of their skin affected than others. Internally, this condition can damage key organs such as the intestines, lungs, heart, and kidneys.

People with diffuse disease often are tired, lose appetite and weight, and have joint swelling or pain. Skin changes can cause the skin to swell, appear shiny, and feel tight and itchy.

The damage of diffuse scleroderma typically occurs over a few years. After the first 3 to 5 years, people with diffuse disease often enter a stable phase lasting for varying lengths of time. During this phase, symptoms subside: joint pain eases, fatigue lessens, and appetite returns. Progressive skin thickening and organ damage decrease.

Gradually, however, the skin may begin to soften, which tends to occur in reverse order of the thickening process: the last areas thickened are the first to begin softening. Some patients’ skin returns to a somewhat normal state, while other patients are left with thin, fragile skin without hair or sweat glands. Serious new damage to the heart, lungs, or kidneys is unlikely to occur, although patients are left with whatever damage they have in specific organs.

People with diffuse scleroderma face the most serious long-term outlook if they develop severe kidney, lung, digestive, or heart problems. Fortunately, less than one-third of patients with diffuse disease develop these severe problems. Early diagnosis and continual and careful monitoring are important.

What Causes Scleroderma?

Although scientists don’t know exactly what causes scleroderma, they are certain that people cannot catch it from or transmit it to others. Studies of twins suggest it is also not inherited. Scientists suspect that scleroderma comes from several factors that may include:

- Genetic makeup. Although genes seem to put certain people at risk for scleroderma and play a role in its course, the disease is not passed from parent to child like some genetic diseases.

- Environmental triggers. Research suggests that exposure to some environmental factors may trigger scleroderma-like disease (which is not actually scleroderma) in people who are genetically predisposed to it. Suspected triggers include viral infections, certain adhesive and coating materials, and organic solvents such as vinyl chloride or trichloroethylene. But no environmental agent has been shown to cause scleroderma. In the past, some people believed that silicone breast implants might have been a factor in developing connective tissue diseases such as scleroderma. But several studies have not shown evidence of a connection.

- Hormones. By the middle-to-late childbearing years (age 30 to 55), women develop scleroderma 7 to 12 times more often than men. Because of female predominance at these and all ages, scientists suspect that hormonal differences between women and men play a part in the disease. However, the role of estrogen or other female hormones has not been proven.

How Is Scleroderma Diagnosed?

Once your doctor has taken a thorough medical history, he or she will perform a physical exam. Finally, your doctor may order lab tests to help confirm a suspected diagnosis. At least two proteins, called antibodies, are commonly found in the blood of people with scleroderma:

- Antitopoisomerase-1 or Anti-Scl-70 antibodies appear in the blood of up to 30% of people with diffuse systemic sclerosis.

- Anticentromere antibodies are found in the blood of many people with limited systemic sclerosis.

A number of other scleroderma-specific antibodies can occur in people with scleroderma, although less frequently. When present, however, they are helpful in clinical diagnosis and may give additional information as to the risks for specific organ problems.

Because not all people with scleroderma have these antibodies and because not all people with the antibodies have scleroderma, lab test results alone cannot confirm the diagnosis.

In some cases, your doctor may order a skin biopsy (the surgical removal of a small sample of skin for microscopic examination) to aid in or help confirm a diagnosis. However, skin biopsies also have their limitations: biopsy results cannot distinguish between localized and systemic disease, for example.

Diagnosing scleroderma is easiest when a person has typical symptoms and rapid skin thickening. In other cases, a diagnosis may take months, or even years, as the disease unfolds and reveals itself and as the doctor is able to rule out some other potential causes of the symptoms. In some cases, a diagnosis is never made, because the symptoms that prompted the visit to the doctor go away on their own.

How Is Scleroderma Treated?

There is currently no treatment that controls or stops the underlying problem, the overproduction of collagen. Thus, treatment and management focus on relieving symptoms and limiting damage.

Your treatment will depend on the particular problems you are having. Some treatments will be prescribed or given by your doctor. Others are things you can do on your own.

Here is a listing of the potential problems that can occur in systemic scleroderma and the medical and nonmedical treatments for them. These problems do not occur as a result or complication of localized scleroderma. This listing is not complete because different people experience different problems with scleroderma and not all treatments work equally well for all people.

Work with your doctor to find the best treatment for your specific symptoms.

Raynaud’s phenomenon

More than 90% of people with scleroderma have this condition, in which the fingers and sometimes other extremities change color in response to cold temperature or anxiety.

If you have Raynaud’s phenomenon, the following measures may make you more comfortable and help prevent problems:

- Don’t smoke! Smoking narrows the blood vessels even more and makes Raynaud’s phenomenon worse.

- Dress warmly, with special attention to hands and feet. Dress in layers and try to stay indoors during cold weather.

- Use biofeedback, which governs various body processes that are not normally thought of as being under conscious control, and relaxation exercises.

- For severe cases, speak to your doctor about prescribing drugs called calcium channel blockers, which can open up small blood vessels and improve circulation. Other drugs are in development and may become available.

- If Raynaud’s phenomenon leads to skin sores or ulcers, increasing your dose of calcium channel blockers (ONLY under the direction of your doctor may help. You can also protect skin ulcers from further injury or infection by applying nitroglycerine paste or antibiotic cream. Severe ulcerations on the fingertips can be treated with bioengineered skin.

Stiff, painful joints

In diffuse systemic sclerosis, hand joints can stiffen because of hardened skin around the joints or inflammation within them. Other joints can also become stiff and swollen.

- Stretching exercises under the direction of a physical or occupational therapist are extremely important to prevent loss of joint motion. These should be started as soon as scleroderma is diagnosed.

- Exercise regularly. Ask your doctor or physical therapist about an exercise plan that will help you increase and maintain range of motion in affected joints. Swimming can help maintain muscle strength, flexibility, and joint mobility.

- Use acetaminophen or an over-the-counter or prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, as recommended by your doctor, to help relieve joint or muscle pain. If pain is severe, speak to a rheumatologist about the possibility of prescription-strength drugs to ease pain and inflammation.

- Learn to do things in a new way. A physical or occupational therapist can help you learn to perform daily tasks, such as lifting and carrying objects or opening doors, in ways that will put less stress on tender joints.

Skin problems

When too much collagen builds up in the skin, it crowds out sweat and oil glands, causing the skin to become dry and stiff. If your skin is affected, try the following:

- Apply moisturizers frequently, and always right after bathing.

- Apply sunscreen before you venture outdoors to protect against further damage from the sun’s rays.

- Use humidifiers to moisten the air in your home in colder winter climates. Clean humidifiers often to stop bacteria from growing in the water.

- Avoid very hot baths and showers, as hot water dries the skin.

- Avoid harsh soaps, household cleaners, and caustic chemicals, if at all possible. Otherwise, be sure to wear rubber gloves when you use such products.

- Exercise regularly. Exercise, especially swimming, stimulates blood circulation to affected areas.

Dry mouth and dental problems

Dental problems are common in people with scleroderma for a number of reasons. Tightening facial skin can make the mouth opening smaller and narrower, which makes it hard to care for teeth; dry mouth caused by salivary gland damage speeds up tooth decay; and damage to connective tissues in the mouth can lead to loose teeth. You can avoid tooth and gum problems in several ways:

- Brush and floss your teeth regularly. If hand pain and stiffness make this difficult, consult your doctor or an occupational therapist about specially made toothbrush handles and devices to make flossing easier.

- Have regular dental checkups. Contact your dentist immediately if you experience mouth sores, mouth pain, or loose teeth.

- If decay is a problem, ask your dentist about fluoride rinses or prescription toothpastes that remineralize and harden tooth enamel.

- Consult a physical therapist about facial exercises to help keep your mouth and face more flexible.

- Keep your mouth moist by drinking plenty of water, sucking ice chips, using sugarless gum and hard candy, and avoiding mouthwashes with alcohol. If dry mouth still bothers you, ask your doctor about a saliva substitute—or prescription medications such as pilocarpine hydrochloride or cevimeline hydrochloride—that can stimulate the flow of saliva.

Gastrointestinal (GI) problems

Systemic sclerosis can affect any part of the digestive system. As a result, you may experience problems such as heartburn, difficulty swallowing, early satiety (the feeling of being full after you’ve barely started eating), or intestinal complaints such as diarrhea, constipation, and gas. In cases where the intestines are damaged, your body may have difficulty absorbing nutrients from food. Although GI problems are diverse, here are some things that might help at least some of the problems you have:

- Eat small, frequent meals.

- To keep stomach contents from backing up into the esophagus, stand or sit for at least an hour (preferably 2 or 3 hours) after eating. When it is time to sleep, keep the head of your bed raised using blocks.

- Avoid late-night meals, spicy or fatty foods, alcohol, and caffeine, which can aggravate GI distress.

- Eat moist, soft foods, and chew them well. If you have difficulty swallowing or if your body doesn’t absorb nutrients properly, your doctor may prescribe a special diet.

- Ask your doctor about prescription medications for problems such as diarrhea, constipation, and heartburn. Some drugs called proton pump inhibitors are highly effective against heartburn. Oral antibiotics may stop bacterial overgrowth in the bowel, which can be a cause of diarrhea in some people with systemic sclerosis.

Lung damage

Virtually all people with systemic sclerosis have some loss of lung function. Some develop severe lung disease, which comes in two forms: pulmonary fibrosis (hardening or scarring of lung tissue because of excess collagen) and pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the artery that carries blood from the heart to the lungs). Treatment for the two conditions is different:

- Pulmonary fibrosis may be treated with drugs that suppress the immune system, such as cyclophosphamide or azathioprine, along with low doses of corticosteroids.

- Pulmonary hypertension may be treated with drugs that dilate the blood vessels, such as prostacyclin, or with newer medications that are prescribed specifically for treating pulmonary hypertension.

Regardless of your particular lung problem or its medical treatment, your role in the treatment process is essentially the same. To minimize lung complications, work closely with your medical team. Do the following:

- Watch for signs of lung disease, including fatigue, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, and swollen feet. Report these symptoms to your doctor.

- Have your lungs closely checked, using standard lung-function tests, during the early stages of skin thickening. These tests, which can find problems at the earliest and most treatable stages, are needed because lung damage can occur even before you notice any symptoms.

- Get the flu vaccines and pneumonia vaccines as recommended by your doctor. Contracting either illness could be dangerous for a person with lung disease.

Heart problems

Common among people with scleroderma, heart problems include scarring and weakening of the heart (cardiomyopathy), inflamed heart muscle (myocarditis), and abnormal heartbeat (arrhythmia). All of these problems can be treated. Treatment ranges from drugs to surgery and varies depending on the nature of the condition.

Kidney problems

Renal crisis occurs in about 10% of all patients with scleroderma, primarily those with early diffuse scleroderma. Renal crisis results in severe uncontrolled high blood pressure, which can quickly lead to kidney failure. It’s very important that you take measures to identify and treat the hypertension as soon as it occurs. These are things you can do:

- Check your blood pressure regularly. You should also check it if you have any new or different symptoms such as a headache or shortness of breath. If your blood pressure is higher than usual, call your doctor right away.

- If you have kidney problems, take your prescribed medications faithfully. In the past two decades, drugs known as ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitors, including captopril, enalapril, and lisinopril, have made scleroderma-related kidney failure a less threatening problem than it used to be. But for these drugs to work, you must take them as soon as the hypertension is present.

Cosmetic problems

Even if scleroderma doesn’t cause any lasting physical disability, its effects on the skin’s appearance—particularly on the face—can take their toll on your self-esteem. Fortunately, there are procedures to correct some of the cosmetic problems scleroderma causes:

- The appearance of telangiectasias—small red spots on the hands and face caused by swelling of tiny blood vessels beneath the skin—may be reduced or even eliminated with the use of guided lasers.

- Facial changes of localized scleroderma—such as the en coup de sabre that may run down the forehead in people with linear scleroderma—may be corrected through cosmetic surgery. (However, such surgery is not appropriate for areas of the skin where the disease is active.)

How Can Scleroderma Affect My Life?

Having a chronic disease can affect almost every aspect of your life, from family relationships to holding a job. For people with scleroderma, there may be other concerns about appearance or even the ability to dress, bathe, or handle the most basic daily tasks. Here are some areas in which scleroderma could intrude.

Appearance and self-esteem: Aside from the initial concerns about health and longevity, people with scleroderma quickly become concerned with how the disease will affect their appearance. Thick, hardened skin can be difficult to accept, particularly on the face. Systemic scleroderma may result in facial changes that eventually cause the opening to the mouth to become smaller and the upper lip to virtually disappear. Linear scleroderma may leave its mark on the forehead. Although these problems can’t always be prevented, their effects may be minimized with proper treatment. Also, special cosmetics—and in some cases plastic surgery—can help conceal scleroderma’s damage.

Caring for yourself: Tight, hard connective tissue in the hands can make it difficult to do what were once simple tasks, such as brushing your teeth and hair, pouring a cup of coffee, using a knife and fork, unlocking a door, or buttoning a jacket. If you have trouble using your hands, consult an occupational therapist, who can recommend new ways of doing things or devices to make tasks easier. Devices as simple as Velcro fasteners and built-up brush handles can help you be more independent.

Family relationships: Spouses, children, parents, and siblings may have trouble understanding why you don’t have the energy to keep house, drive to soccer practice, prepare meals, or hold a job the way you used to. If your condition isn’t that visible, they may even suggest you are just being lazy. On the other hand, they may be overly concerned and eager to help you, not allowing you to do the things you are able to do or giving up their own interests and activities to be with you. It’s important to learn as much about your form of the disease as you can and to share any information you have with your family. Involving them in counseling or a support group may also help them better understand the disease and how they can help you.

Sexual relations: Sexual relationships can be affected when systemic scleroderma enters the picture. For men, the disease’s effects on the blood vessels can lead to problems achieving an erection. For women, damage to the moisture-producing glands can cause vaginal dryness that makes intercourse painful. People of either sex may find they have difficulty moving the way they once did. They may be self-conscious about their appearance or afraid that their sexual partner will no longer find them attractive. With communication between partners, good medical care, and perhaps counseling, many of these changes can be overcome or at least worked around.

Pregnancy and childbearing: In the past, women with systemic scleroderma were often advised not to have children. But thanks to better medical treatments and a better understanding of the disease itself, that advice is changing. (Pregnancy, for example, is not likely to be a problem for women with localized scleroderma.) Although blood vessel involvement in the placenta may cause babies of women with systemic scleroderma to be born early, many women with the disease can have safe pregnancies and healthy babies if they follow some precautions.

One of the most important pieces of advice is to wait a few years after the disease starts before attempting a pregnancy. During the first 3 years, you are at the highest risk of developing severe problems of the heart, lungs, or kidneys that could be harmful to you and your unborn baby.

If you haven’t developed severe organ problems within 3 years of the disease’s onset, your chances of such problems are less and pregnancy would be safer. But it is important to have both your disease and your pregnancy monitored regularly. You’ll probably need to stay in close touch with both the doctor you typically see for your scleroderma and an obstetrician who is experienced in guiding high-risk pregnancies.

Source: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

Last updated : 1/8/2019