The Spine and Vertebrae

The Spine and Vertebrae

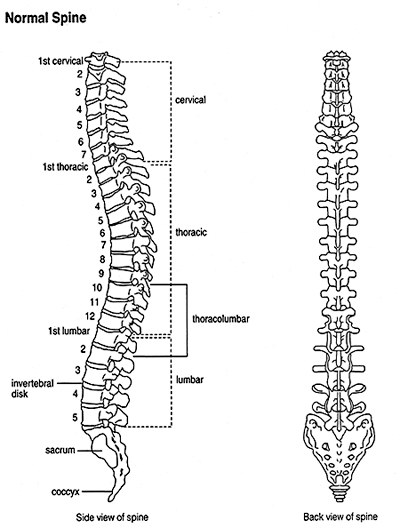

The spine (or backbone) is a column of 26 bones called vertebrae that extend in a line from the base of the skull to the pelvis. This is referred to as the "spinal column" or "vertebral column". The spinal column provides the main support for the upper body, allowing humans to stand upright or bend and twist, and it protects the spinal cord from injury.

The lower part of the back holds most of the body's weight. Even a minor problem with the bones, muscles, ligaments, or tendons in this area can cause pain when a person stands, bends, or moves around. Less often, a problem with a disc can pinch or irritate a nerve from the spinal cord, causing pain that runs down the leg, below the knee, called sciatica.

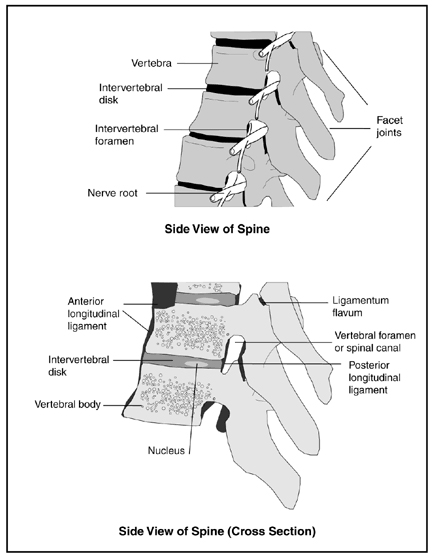

Each vertebrae has a circular opening similar to the hole in a donut. The bones are stacked one on top of one another, and the spinal cord runs through the hollow channel created by the holes in the stacked bones.

Nerves from the spinal cord branch out and leave the spine through the spaces between the vertebrae.

The vertebrae can be organized into sections, and are named and numbered from top to bottom according to their location along the backbone:

- Cervical vertebrae (1-7) located in the neck

- Thoracic vertebrae (1-12) in the upper back (attached to the ribcage)

- Lumbar vertebrae (1-5) in the lower back

- Sacral vertebrae (1-5) in the hip area

- Coccygeal vertebrae (1-4 fused) in the tailbone

Components of each vertebrae that are important for normal function include the following:

Components of each vertebrae that are important for normal function include the following:

- Intervertebral disks—pads of cartilage filled with a gel-like substance which lie between vertebrae and act as shock absorbers.

- Facet joints—joints located on the back of the main part of the vertebra. They are formed by a portion of one vertebra and the vertebra above it. They connect the vertebrae to each other and permit backward motion.

- Intervertebral foramen (also called neural foramen)—an opening between vertebrae through which nerves leave the spine and extend to other parts of the body.

- Lamina—part of the vertebra at the back portion of the vertebral arch that forms the roof of the canal through which the spinal cord and nerve roots pass.

- Ligaments—elastic bands of tissue that support the spine by preventing the vertebrae from slipping out of line as the spine moves. A large ligament often involved in spinal stenosis is the ligamentum flavum, which runs as a continuous band from lamina to lamina in the spine.

- Pedicles—narrow stem-like structures on the vertebrae that form the walls of the front part of the vertebral arch.

- Spinal cord/nerve roots—a major part of the central nervous system that extends from the base of the brain down to the lower back and that is encased by the vertebral column. It consists of nerve cells and bundles of nerves. The cord connects the brain to all parts of the body via 31 pairs of nerves that branch out from the cord and leave the spine between vertebrae.

- Synovium—a thin membrane that produces fluid to lubricate the facet joints, allowing them to move easily.

- Vertebral arch—a circle of bone around the canal through which the spinal cord passes. It is composed of a floor at the back of the vertebra, walls (the pedicles), and a ceiling where two laminae join.

- Cauda equina—a sack of nerve roots that continues from the lumbar region, where the spinal cord ends, and continues down to provide neurologic function to the lower part of the body. It resembles a "horse's tail" (cauda equina in Latin).

The Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is also cushioned by a fluid called Cerebral Spinal Fluid (CSF), which protects the delicate nerve tissues from being damaged by rubbing against the inside of the vertebrae.

Although the hard vertebrae and CSF protect the soft spinal cord from injury most of the time, the spinal column is not all hard bone. Between the vertebrae are discs of semi-rigid cartilage, and in the narrow spaces between them are passages through which the spinal nerves exit to the rest of the body. These are places where the spinal cord is vulnerable to direct injury.

Like the vertebrae, the spinal cord is also organized into segments and named and numbered from top to bottom. Each segment marks where spinal nerves emerge from the cord to connect to specific regions of the body. Locations of spinal cord segments do not correspond exactly to vertebral locations, but they are roughly equivalent.

- Cervical spinal nerves (C1 to C8) control signals to the back of the head, the neck and shoulders, the arms and hands, and the diaphragm.

- Thoracic spinal nerves (T1 to T12) control signals to the chest muscles, some muscles of the back, and parts of the abdomen.

- Lumbar spinal nerves (L1 to L5) control signals to the lower parts of the abdomen and the back, the buttocks, some parts of the external genital organs, and parts of the leg.

- Sacral spinal nerves (S1 to S5) control signals to the thighs and lower parts of the legs, the feet, most of the external genital organs, and the area around the anus.

- The single coccygeal nerve carries sensory information from the skin of the lower back.

The functions of these nerves are determined by their location in the spinal cord. They control everything from body functions such as breathing, sweating, digestion, and elimination, to gross and fine motor skills, as well as sensations in the arms and legs.

An injury to the spinal cord may inhibit the functioning of any nerves located below the site of injury.

The Spinal Cord and Nervous System

Although the brain often gets most of the credit for being the "central processing unit" of the body, the spinal cord also plays a crucial role in what is known as the central nervous system (CNS). The CNS controls most functions of the body, including movement, organ functions, and behavior.

The spinal cord descends from the brain down the middle of the back, and acts as the primary information pathway between the brain and all the other nervous systems of the body. It receives sensory information from the skin, joints, and muscles of the trunk, arms, and legs, which it then relays upward to the brain. It also contains motor neurons, which direct voluntary movements and adjust reflex movements. Because of the central role it plays in coordinating muscle movements and interpreting sensory input, any kind of spinal cord injury can cause significant problems throughout the body.

The CNS communicates with the limbs, heart, skin, muscles, and other organs of the body through a network of nerves collectivly known as the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Most of the nerves of the PNS connect to the spinal cord at various locations up and down the back.

The PNS controls the somatic nervous system, which regulates muscle movements and the response to sensations of touch and pain, and the autonomic nervous system, which provides nerve input to the internal organs and generates automatic reflex responses.

The autonomic nervous system is itself divided into the sympathetic nervous system, which mobilizes organs and their functions during times of stress and arousal ("fight or flight"), and the parasympathetic nervous system, which conserves energy and resources during times of rest and relaxation ("rest and digest").

Spinal Cord Physiology

The interior of the spinal cord is made up of neurons, their support cells called glia, and blood vessels. The neurons and their dendrites (branching projections that help neurons communicate with each other) reside in an H-shaped region called "grey matter."

The H-shaped grey matter of the spinal cord contains motor neurons that control movement, smaller interneurons that handle communication within and between the segments of the spinal cord, and cells that receive sensory signals and then send information up to centers in the brain.

Surrounding the grey matter of neurons is white matter. Most axons are covered with an insulating substance called myelin, which allows electrical signals to flow freely and quickly. Myelin has a whitish appearance, which is why this outer section of the spinal cord is called "white matter." A number of diseases damage the myelin and the white matter, including multiple sclerosis and postinfectious encephalomyelitis.

Axons carry signals downward from the brain (along descending pathways called efferent nerves) and upward toward the brain (along ascending pathways called afferent nerves) within specific tracts. Axons branch at their ends and can make connections with many other nerve cells simultaneously. Some axons extend along the entire length of the spinal cord.

The descending motor tracts control the smooth muscles of internal organs and the striated (capable of voluntary contractions) muscles of the arms and legs. They also help adjust the autonomic nervous system's regulation of blood pressure, body temperature, and the response to stress. These pathways begin with neurons in the brain that send electrical signals downward to specific levels of the spinal cord. Neurons in these segments then send the impulses out to the rest of the body or coordinate neural activity within the cord itself.

The ascending sensory tracts transmit sensory signals from the skin, extremities, and internal organs that enter at specific segments of the spinal cord. Most of these signals are then relayed to the brain. The spinal cord also contains neuronal circuits that control reflexes and repetitive movements, such as walking, which can be activated by incoming sensory signals without input from the brain.

The circumference of the spinal cord varies depending on its location. It is larger in the cervical and lumbar areas because these areas supply the nerves to the arms and upper body and the legs and lower body, which require the most intense muscular control and receive the most sensory signals.

The circumference of the spinal cord varies depending on its location. It is larger in the cervical and lumbar areas because these areas supply the nerves to the arms and upper body and the legs and lower body, which require the most intense muscular control and receive the most sensory signals.

The ratio of white matter to grey matter also varies at each level of the spinal cord. In the cervical segment, which is located in the neck, there is a large amount of white matter because at this level there are many axons going to and from the brain and the rest of the spinal cord below. In lower segments, such as the sacral, there is less white matter because most ascending axons have not yet entered the cord, and most descending axons have contacted their targets along the way. To pass between the vertebrae, the axons that link the spinal cord to the muscles and the rest of the body are bundled into 31 pairs of spinal nerves, each pair with a sensory root and a motor root that make connections within the grey matter. Two pairs of nerves - a sensory and motor pair on either side of the cord - emerge from each segment of the spinal cord.

Source: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

Last updated : 5/13/2022